| FRANCAIS | ||||||

| RESUME | REVIEWS | INFO | CCINQ | DECADE | MAISON COMMUN |

Writing is always the starting point. Writing which highlights the word that says the absence. Whether it is in my films, in my installations, my sculptures or during performances, I am always constructing a simple story centered on the observation of language by ways of antinomy. |

By observing the unspoken I am questioning the discourse. By all means the silence will be sought as a counter-speech, which becomes a sign in itself. Out of the comprehensive study of the recording of Roland Barthes’classes on "Neutral" (Collège de France 1977-1978), |

an experiment is emerging that increasingly bypasses the meaning or the opposition. Foil the paradigm. Man disappears increasingly to keep the object or the image away from the viewer, to accentuate the distance between the subject and its meaning. |

Going towards the suspension of conflicting speech datas and prefering an arrangement sliding towards abstraction. An effort in difference. An order of nuance. It is about organizing without opposition. |

|

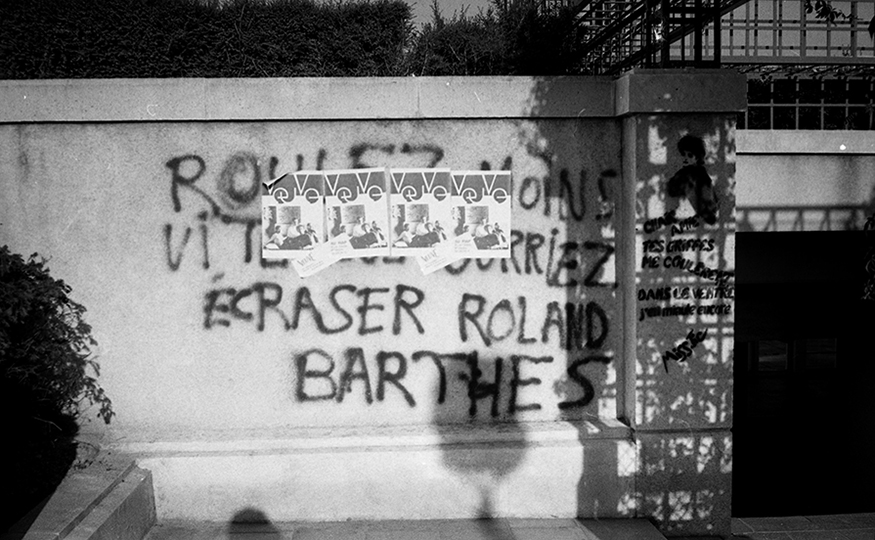

Slow down you could hit Roland Barthes (Roulez moins vite vous pourriez écraser Roland Barthes). This installation stems from the discovery of a photograph taken in France in the early 1980s. |

It’s an image of graffiti which makes reference to semiologist Roland Barthes’ death (photography Alain Dodeler). As in my previous work, this urban light installation performs a movement translating image into sculpture. |

Speech is the central element of this installation. However, rather than concentrating on the meaning of words themselves, the approach taken here gives more importance to the temporal and geographical concreteness of words. Whenever a string of letters enters our field of vision, we begin reading them, whether voluntarily or subconsciously. In a similar manner, hearing words conjures up images which can distract us either for an instant or a longer stretch of time. Yet a gap exists between our mechanism for understanding and our actual realization. |

This disparity can be easily perceived when one is faced with a foreign linguistic environment. By highlighting it, the aim is to play on a cultural disorientation rather than the meaning of the words themselves.

This work is an invitation to a momentary and poetic disconnect, an intellectual disassociation in its most authentic form. |

|

|

|

I went to Herman Daled’s house for the first time in 2015 during my residency at Wiels Contemporary Art Centre, Brussels. The meeting was organised with this man who, upon discovering Marcel Broodthaers, had become one of the most important collectors of conceptual art in Belgium. |

During the visit, one thing struck me. Daled didn’t have any works of art hanging in his house. While navigating the conceptual art movement, Daled had gleaned works that he conserved not as objects of pleasure but as objects of knowledge. His walls were adorned only with nails. I was surprised, shocked, touched. I saw a certain poetry there. |

When I was asked to create an edition for Island gallery, an amusing idea came to me. The idea amused me for both its subtlety and the meaning I could give to it. It was an idea that could be mischievous and poetic, simultaneously. I decided to go back to Herman Daled and borrow one of his nails that I’d seen on his walls, and make a mold from it then reproduce it 100 times. |

It only seemed natural to use silver to make the nails. Indeed, Daled was a radiologist and of course, silver is used to create negative images. It was all was there

Untitled (silver), 2018, silver, 2.8 x 0,4 cm x 0.8 gr, 100 ex +AP |

|

Most of Giorgio Morandi’s oeuvre is made up of still lifes, painted as a series of variations on the same theme. |

He stages different objects in a line: bottles, bowls, perhaps a shell or some fruit from time to time – all in monochromatic tones, endlessly repeating the same angles on a table or a shelf. In each still life lies a recurring and mysterious object which stands out from the rest by means of its lack of use. It’s a kind of solid brick, a matte cuboid that has nothing to do with traditional still life painting. It appears in different sizes and colours and contrasts as a fake object amongst real ones. Were these parallelepipeds there to simply ward off boredom and banality? |

Was their use to give solidity and strangeness to the composition? At a moment of estrangement, when utility had vanished, I started to reproduce the parallelepipeds in clay. In one way or another, I wanted to make them remarkable. I gave them – as in the still lifes – a sense of delicate virtue. A “silent life” that would reflect an inner life. The process became a ritual from which other simple geometrical forms were born, mostly cylinders. In research, if one concentrates one’s attention on shape and colour, the ease of a group of objects sat on a table is seductive. |

The step towards a disconcertingly simple stacking of the pieces was therefore logic – it led to the possible multiple readings of an inner landscape that stood upright, imperfect, wavering. They held each other. These objects – “statues” – rose and became prayers.

Stack Nr 1, 2, 3 , 2016, Ceramics |

|

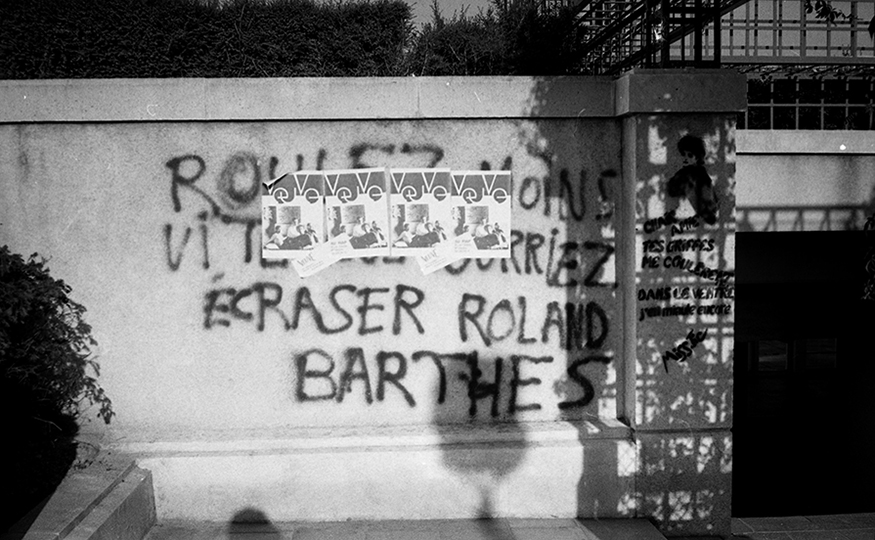

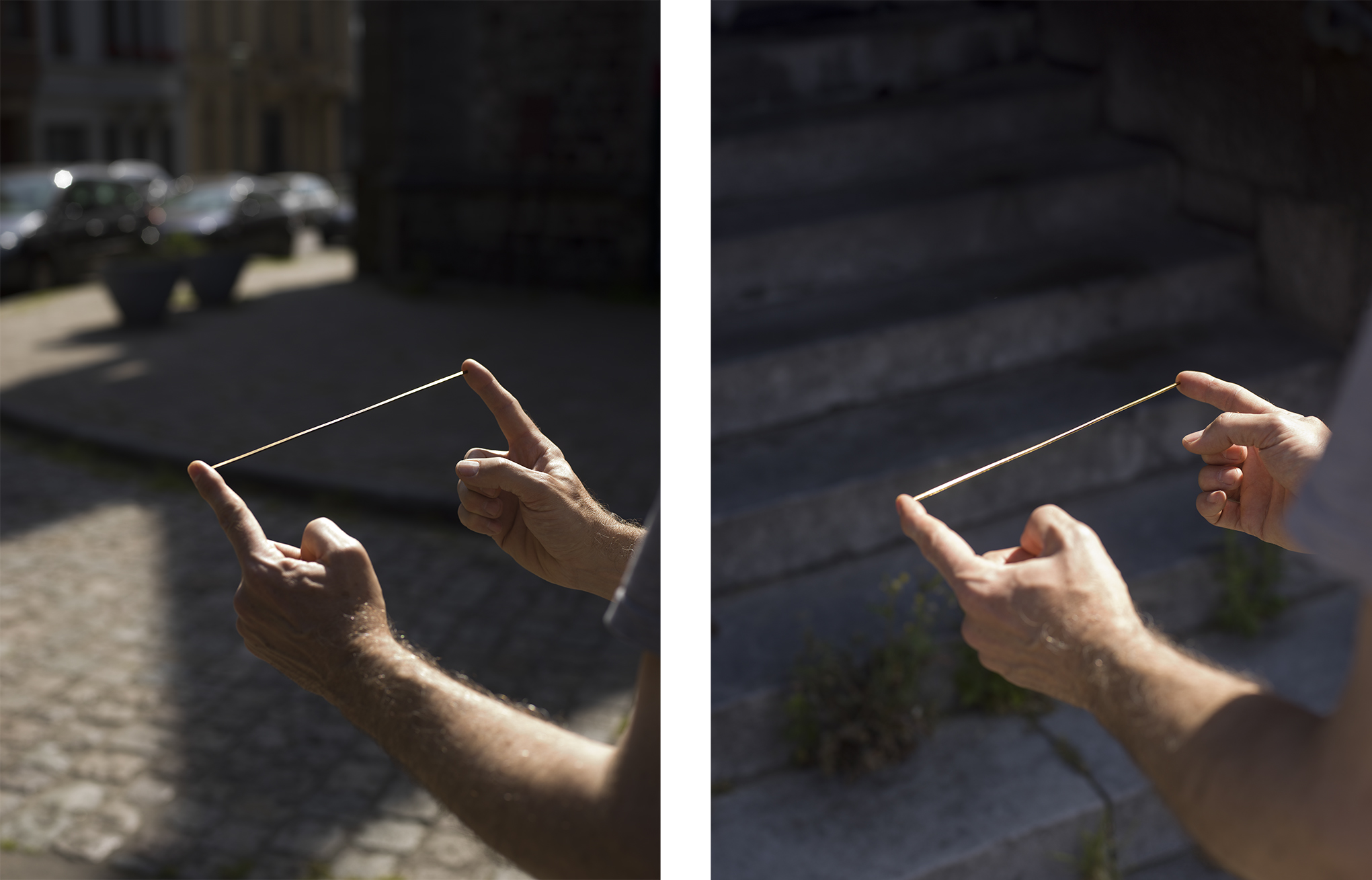

In 2013 I made a sculpture that was to become a key element in my artistic practice. Disappearance, absence, and transmission – themes which lie at the centre of creating an artwork – are united in one, extremely minimal, object. |

Timeline is made up of jewelery I inherited from my mother. The pieces are melted down then stretched out to a length which is determined by the quantity of matter available. |

lay the foundations for an ever-persistent quest to develop an otherness that could question its own individuality and collective essence simultaneously.

Since, I have never stopped expressing time. |

I’m conscious that an irreversible countdown has started. Death has become real. This is a total awakening. The subject matter has been declared and it is defined by age. A moment in time, an initiation, a discovery: I am mortal.

Timeline, 2016, gold, 27 x 0.2 x 0.2 cm |

|

When I was eight years old, I would tell people I was Russian. I don’t remember why nor when it all started, I just remember that for a while as a kid I would do strange things like wearing two different coloured shoe laces. |

I said it was because that’s how the Russians wore them. And as I was Russian, so did I. I had invented a kind of heterotopia that allowed me to apprehend the space I belonged to differently. As I couldn’t go elsewhere, I transformed by everyday reality into an alternative space. |

It went as far as my teacher giving me a book on sport entirely written in Russian. The book was mostly made up of images of children and teens doing sports in a carefree Soviet Republic. |

Without that book which acts somehow as a marker, the period would certainly have disappeared from my memory.

CCCP MOCKBA, 2018, Print blue on poplar, 122 x 79 cm |

|

In early 2018, while taking part in the Academia Belgica’s residency program in Rome, a friend messaged me a link to a news report on the Franco-German TV channel Arte. It was about solidarity for the migrants who were camped out at Brussels’ Maximilien park, and the civic endeavor to house them over the winter. |

I knew she was very much involved in the movement and so expected to see her in the show. “Make sure you watch right until the end,” she had said. Instead, in a bedroom destined to house a migrant for the night, I was surprised to see a poster I’d made during my residency at |

Wiels Contemporary Art Centre in Brussels pinned up on the wall above the bed: “Blinded by the lights”. Things seemed to take on a new meaning at a time when I was asking myself about usefulness; and after all it’s recurring question. |

Simply writing down words and sentences and putting them out in the world suddenly had an unexpected value.

Blinded by the lights, 2015 Print on paper, 70 x 100 cm |

|

It was the early 2000’s. I was visiting a friend incarcerated in a correctional facility. Most of the visitors were mothers who had come with their children. They were all waiting. |

The women spoke to each other and the kids played. This big visiting room was a playground for them, bathed in early sunlight that flooded through the big, open windows.

A small group of men dressed in a light grey uniform came into the room and split up as each one found a familiar face. Voices and cries echoed around the room. Children ran around, in between the legs of their fathers or older brothers. Everything came alive. My friend walked towards our table, smiling, happy to see me.

A bell rang, announcing the end of visiting hours — a little like the one you’d hear at the end of break time in a school yard — and I noticed a reproduction on one of the walls of a Caspar Friedrich painting. It was one I knew well as I’d come across it during my studies: Chalk Cliffs on Rügen. |

In 2012, a few days before leaving to an artists’ residency on Comacina island, a sudden need to see Friedrich’s painting came over me for no particular reason. I quickly discovered it was hanging in the Oskar Reinhart collection in Winterthur. According to the map, I would be driving past Winterthur on my way down to Comacina.

I arrived at the museum an hour before closing time, so the cashier gave me a reduced-price ticket.

Just a few seconds after I sat down in front of the painting, a bell rang, announcing the end of visiting hours.

A guard came and asked me to make my way towards the exit. I got back in the car and drove until sunset. |

I parked at the roadside and fell asleep in the car.

At dawn, I realised I had unknowingly parked facing a play area.

I found it strange, deserted in the bluish morning light. Timeless.

I picked up my Rollei 35 and took what was the first photo of the “Morning's Playground” series. |

|

|

|

In 2006 I started using an SX-70 camera and gave myself a simple protocol to follow: only shoot unknown young men in the street, if possible keeping the same framing and composition. This lasted quite a while. |

I remember I started in Liverpool at the beginning of Spring. The sun was shining, it was really cold and the sky very blue. As I didn’t know the camera so well, I began to play around with it, to get used to it. I accidentally pressed the shutter button and out came my first ever Polaroid photo along with an unexpected noise. It was blue. I understood right then that I wouldn’t just be doing portraits. My second photo was of a boy on Hope Street. |

He was the first one I asked. He said yes without hesitation and posed. I told him not to do anything else. I think that might be one of my favorite photos. Not because it’s the first one of a boy but because something out of my control really happened. He took that photo. I was just in the right place at the right time. I’m not the kind of person who takes a lot of photos, even though I always had the SX-70 in my bag back then. |

I often think “oh I should have taken that photo”, but it’s already too late. In the end, what’s difficult is to really be there and catch the changing light and the passing boys. These photos are traces of such moments.

Daylight, Polaroid, 2006-2011 |

|

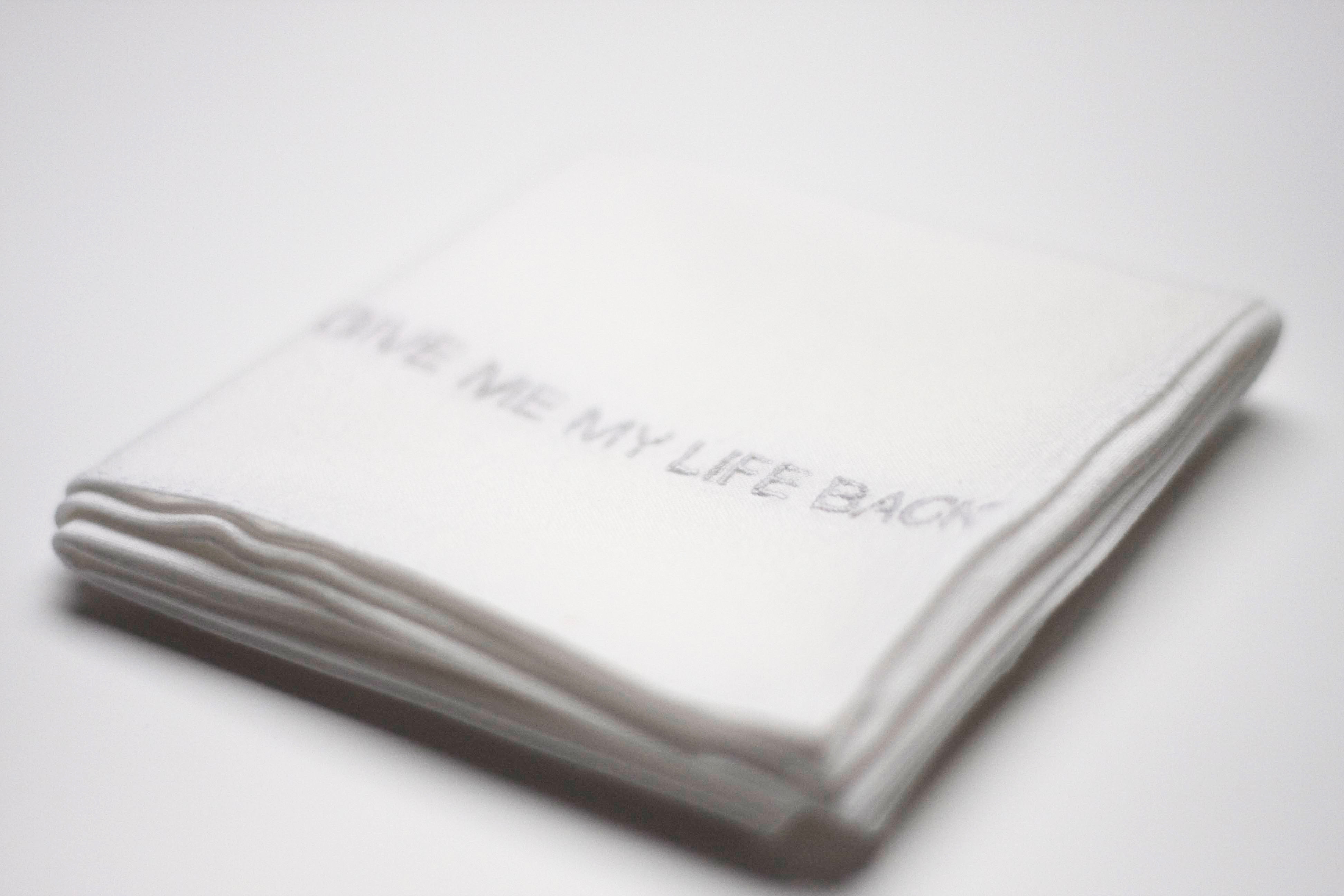

In December 2008 I began a film adaptation of Georg Büchner’s play, “Woyzeck”. The plot is based on the true story of an unemployed ex-soldier who was accused of murdering his lover and subsequently sentenced to death then beheaded in Leipzig. |

In order to create a contemporary narrative, I began weaving a storyline from various sources of inspiration: news items, diaries, literary classics, and archives. This research led me to read Death Row prisoner files from the State of Texas which contained transcripts of the offenders’ last statements. |

The reports began in 1982 and came to a total of 447 in 2008.

Having read these reports, I decided to look closely at what is said just before “the end”. |

I began to quite literally shed light on some of these last words.

Take me back, 2011, White cotton, white silk, 42 x 42 cm |

|

| Top |

|

|